A wise college coach football coach once said to me: “In a ham and egg breakfast, the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed.”

I thought a lot about commitment as I stood on the exit of Sonoma’s turn 3-3a complex for Sunday’s morning warm up. As the cool of the morning began to ebb, and the shrill howl of twin turbos sliced through the air, I watched 22 drivers approach the same corner, looking for truth in tenths of seconds.

What I saw proved the old coach’s point. Turn 3-3a is a devilish left-right flick: entered from a downhill slope out of Turn 2, the turn dives left, then climbs up and slightly to the right on exit. On the other side is a long downhill straight, putting a premium on exit speed out of 3a. Imagine the Corkscrew at Laguna Seca, taken in reverse. The entry is fast, the car leaning left as the driver muscles it to the right, all while standing on the throttle. It’s a lesson in commitment and which drivers have, as they say, “rather large attachments”.

Team Penske’s Will Power and Juan Pablo Montoya come through early, Montoya carrying tremendous exit speed and the raw aggression that has won him races at Monaco, Indianapolis, and Daytona. Power shows more nuance but no less speed through the same complex. Castroneves isn’t far off from his stablemates. Then the Ganassi cars appear, Dixon and Kanaan just a blur in their red and white Target cars, fully dialed in. Although Power is the polesitter, Dixon and Kanaan look quick in morning warm up.

Later, much later, as Dixon stalked Mike Conway for the lead in the waning laps of the race, a Chevrolet engineer attached to Conway’s team explained Dixon’s pace: “Dixon rolls the car through the corner like nobody else. Carries more speed into, and out of, the corners.” It also helps conserve fuel, which ended up costing Kanaan a shot at winning the race.

Then it’s time for the Andretti drivers to take on 3-3a. Hinchcliffe is slow getting out of the garage, but Ryan Hunter-Reay is in full attack mode. The engine coughs, sputters and blurps as Hunter-Reay bumps against the rev limiter, pushed beyond its limits by the aero load and the demands of the driver’s right foot. Gravity wants to send the car into the sky; locked in an eternal struggle with its opposite number, downforce, which wants to plant the car and compress the driver into his seat. The Firestone tires scream in anger, testing the limits of adhesion.

And that’s how you know who is committed. Guys on the rev limiter are pushing hard, making the corner work for them, using all of their skills and relying on bravery for the rest. A group of cars come through that are off the rev limiter, who are fighting the car and the corner, whose revs drop as they struggle with the sudden change of direction. The newer drivers struggle the most, Munoz, Huertas and Saavedra look lost at sea. They choose a different apex than Power and Dixon, setting up more for the entry than the exit, where speed matters more.

There are critical tenths to be picked up at corners like this; tenths that mean the difference between P1 and P20. Never leave something on the table. Wily veterans know this. Young drivers have to learn.

A group of drivers who occassionally get 3-3a right come through. Graham Rahal and Sebastien Bourdais are quick on occasion, like Sato and Conway, but none can pull of the kind of metronomic consistency that guys like Power and Dixon display lap after lap.

And in that sense, Turn 3-3a presents a microcosm of the IndyCar pecking order, a hierarchy revealed in a single turn. The quick and the ballsy tend to be with the elite teams; the rest struggle for consistency from week to week. You can see why Power does so well at Sonoma: he’s quick, but he’s off the rev limiter, which means he knows the precise mixture of steering input and throttle for quick in-quick out. It’s the smoothness that won him pole, a course record, three wins and a second at this circuit. Dixon used the same skills to pull out a win after Power faltered in the race.

It’s all a matter of commitment.

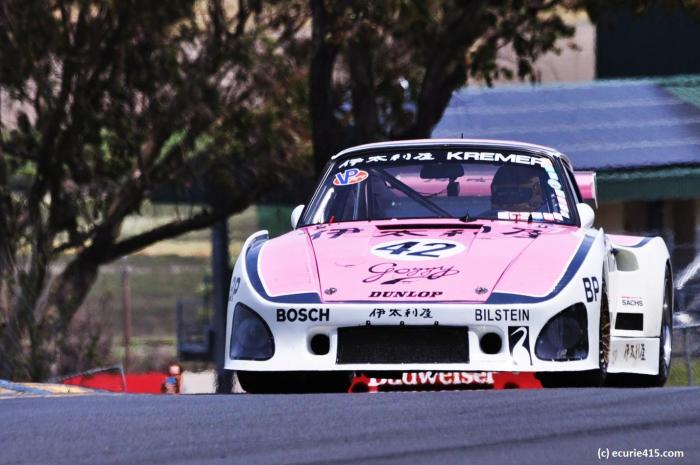

Illustration: Ryan Briscoe approaching Turn 2 at Sonoma, with the Turn 3 just beyond. Below, Hunter-Reay exits 3a.

Look at Kanaan’s head in the photos above and below to get a sense of the lateral forces opposing him as he exits the corner.

The turn exits to a downhill straight. Exit speed is key.

****